Joseph Pulitzer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Joseph Pulitzer ( ; born Pulitzer József, ; April 10, 1847 – October 29, 1911) was a Hungarian-American politician and newspaper publisher of the ''

In the ''Westliche Post'' building, Pulitzer made the acquaintance of attorneys William Patrick and Charles Phillip Johnson and surgeon Joseph Nash McDowell. Patrick and Johnson referred to Pulitzer as "

In the ''Westliche Post'' building, Pulitzer made the acquaintance of attorneys William Patrick and Charles Phillip Johnson and surgeon Joseph Nash McDowell. Patrick and Johnson referred to Pulitzer as "

In 1895,

In 1895,

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

The ''St. Louis Post-Dispatch'' is a major regional newspaper based in St. Louis, Missouri, serving the St. Louis metropolitan area. It is the largest daily newspaper in the metropolitan area by circulation, surpassing the ''Belleville News-De ...

'' and the ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under publi ...

''. He became a leading national figure in the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

and was elected congressman from New York. He crusaded against big business and corruption and helped keep the Statue of Liberty

The Statue of Liberty (''Liberty Enlightening the World''; French: ''La Liberté éclairant le monde'') is a List of colossal sculpture in situ, colossal neoclassical sculpture on Liberty Island in New York Harbor in New York City, in the U ...

in New York.

In the 1890s the fierce competition between his ''World'' and William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

's ''New York Journal

:''Includes coverage of New York Journal-American and its predecessors New York Journal, The Journal, New York American and New York Evening Journal''

The ''New York Journal-American'' was a daily newspaper published in New York City from 1937 t ...

'' caused both to develop the techniques of yellow journalism

Yellow journalism and yellow press are American terms for journalism and associated newspapers that present little or no legitimate, well-researched news while instead using eye-catching headlines for increased sales. Techniques may include e ...

, which won over readers with sensationalism, sex, crime and graphic horrors. The wide appeal reached a million copies a day and opened the way to mass-circulation newspapers that depended on advertising revenue (rather than cover price or political party subsidies) and appealed to readers with multiple forms of news, gossip, entertainment and advertising.

Today, his name is best known for the Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

s, which were established in 1917 as a result of his endowment to Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

. The prizes are given annually to recognize and reward excellence in American journalism, photography, literature, history, poetry, music, and drama. Pulitzer founded the Columbia School of Journalism

The Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism is located in Pulitzer Hall on the university's Morningside Heights campus in New York City.

Founded in 1912 by Joseph Pulitzer, Columbia Journalism School is one of the oldest journalism sc ...

by his philanthropic bequest; it opened in 1912.

Early life

He was born as Pulitzer József (name order by Hungarian custom) inMakó

Makó (, german: Makowa, yi, מאַקאָווע Makowe, ro, Macău or , sk, Makov) is a town in Csongrád County, in southeastern Hungary, from the Romanian border. It lies on the Maros River. Makó is home to 23,272 people and it has an area ...

, about 200 km south-east of Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

, the son of Elize (Berger) and Fülöp Pulitzer (born Politzer). The Pulitzers were among several Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

families living in the area and had established a reputation as merchants and shopkeepers. Joseph's father was a respected businessman, regarded as the second of the "foremost merchants" of Makó. Their ancestors emigrated from Police

The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state, with the aim to enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder. Their lawful powers include arrest and t ...

in Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The me ...

to Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

at the end of the 18th century.

In 1853, Fülöp Pulitzer was rich enough to retire. He moved his family to Pest, where he had the children educated by private tutors, and taught French and German. In 1858, after Fülöp's death, his business went bankrupt, and the family became impoverished. Joseph attempted to enlist in various European armies for work before emigrating to the United States.

Civil War service

Pulitzer tried to join the military but was rejected by theAustrian Army

The Austrian Armed Forces (german: Bundesheer, lit=Federal Army) are the combined military forces of the Republic of Austria.

The military consists of 22,050 active-duty personnel and 125,600 reservists. The military budget is 0.74% of nati ...

, he then tried to join the French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (french: Légion étrangère) is a corps of the French Army which comprises several specialties: infantry, Armoured Cavalry Arm, cavalry, Military engineering, engineers, Airborne forces, airborne troops. It was created ...

to fight in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

but was similarly rejected, and then the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

where he was also rejected. He was finally recruited in Hamburg, Germany, to fight for the Union in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

in August 1864. Pulitzer could not speak English when he arrived in Boston Harbor in 1864 at the age of 17, his passage having been paid by Massachusetts military recruiters. Learning that the recruiters were pocketing the lion's share of his enlistment bounty, Pulitzer left the Deer Island recruiting station and made his way to New York. He was paid $200 to enlist in the Lincoln Cavalry on September 30, 1864. He was a part of Sheridan's troopers, in the 1st New York Cavalry Regiment in Company L, joining the regiment in Virginia in November 1864, and fighting in the Appomattox Campaign, before being mustered out on June 5, 1865. Although he spoke German, Hungarian, and French, Pulitzer learned little English until after the war, as his regiment was composed mostly of German immigrants.

Early career in St. Louis

After the war, Pulitzer returned to New York City, where he stayed briefly. He moved toNew Bedford

New Bedford (Massachusett: ) is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast region. Up through the 17th century, the area was the territory of the Wampanoag Native American pe ...

, Massachusetts, for the whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industry ...

industry, but found it was too boring for him. He returned to New York with little money. Flat broke, he slept in wagons on cobblestone side streets. He decided to travel by "side-door Pullman" (a freight boxcar) to St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

. He sold his one possession, a white handkerchief, for 75 cents.

When Pulitzer arrived at the city, he recalled, "The lights of St. Louis looked like a promised land to me." In the city, his German was as useful as it was in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

because of the large ethnic German population, due to strong immigration since the revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

. In the ''Westliche Post

''Westliche Post'' (literally ''"Western Post"'') was a German-language daily newspaper published in St. Louis, Missouri. The ''Westliche Post'' was Republican in politics. Carl Schurz was a part owner for a time, and served as a U.S. Senator f ...

'', he saw an ad for a mule hostler at Benton Barracks

Benton Barracks (or Camp Benton) was a Union Army military encampment, established during the American Civil War, in St. Louis, Missouri, at the present site of the St. Louis Fairground Park. Before the Civil War, the site was owned and used by th ...

. The next day he walked four miles and got the job, but held it for only two days. He quit due to the poor food and the whims of the mules, stating "The man who has not cared for sixteen mules does not know what work and troubles are." Pulitzer had difficulty holding jobs; he was too scrawny for heavy labor and likely too proud and temperamental to take orders.

He worked as a waiter at ''Tony Faust,'' a famous restaurant on Fifth Street. It was frequented by members of the St. Louis Philosophical Society, including Thomas Davidson, the German Henry C. Brockmeyer; and William Torrey Harris

William Torrey Harris (September 10, 1835 – November 5, 1909) was an American educator, philosopher, and lexicographer. He worked for nearly a quarter century in St. Louis, Missouri, where he taught school and served as Superintendent of Sch ...

. Pulitzer studied Brockmeyer, who was famous for translating Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends a ...

, and he "would hang on Brockmeyer's thunderous words, even as he served them pretzels and beer." He was fired after a tray slipped from his hand and a patron was soaked in beer.

Pulitzer spent his free time at the St. Louis Mercantile Library

The St. Louis Mercantile Library, founded in 1846 in downtown St. Louis, Missouri, was originally established as a membership library, and is the oldest extant library west of the Mississippi River. Since 1998 the library has been housed at the ...

on the corner of Fifth and Locust, studying English and reading voraciously. He made a lifelong friend there in the librarian Udo Brachvogel. He often played in the library's chess room, where Carl Schurz noticed his aggressive style. Pulitzer greatly admired the German-born Schurz, an emblem of the success attainable by a foreign-born citizen through his own energies and skills. In 1868, Pulitzer was admitted to the bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

, but his broken English and odd appearance kept clients away. He struggled with the execution of minor papers and the collecting of debts. That year, when the ''Westliche Post'' needed a reporter, he was offered the job.

Soon after, he and several dozen men each paid a fast-talking promoter five dollars, after being promised good-paying jobs on a Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

sugar plantation. They boarded a steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. Steamboats sometimes use the ship prefix, prefix designation SS, S.S. or S/S ...

, which took them downriver 30 miles south of the city, where the crew forced them off. When the boat churned away, the men concluded the promised plantation jobs had been a ruse. They walked back to the city, where Pulitzer wrote an account of the fraud and was pleased when it was accepted by the ''Westliche Post'', edited by Dr. Emil Preetorius

Emil Preetorius (15 March 1827 – 19 November 1905) was a 19th-century journalist from St. Louis. He was a leader of the German American community as part owner and editor of the ''Westliche Post'', one of the most notable and well-circulated ...

and Carl Schurz, evidently his first published news story.

On March 6, 1867, Pulitzer became a naturalized American citizen

Citizenship of the United States is a legal status that entails Americans with specific rights, duties, protections, and benefits in the United States. It serves as a foundation of fundamental rights derived from and protected by the Constituti ...

.

Entry to journalism and politics

In the ''Westliche Post'' building, Pulitzer made the acquaintance of attorneys William Patrick and Charles Phillip Johnson and surgeon Joseph Nash McDowell. Patrick and Johnson referred to Pulitzer as "

In the ''Westliche Post'' building, Pulitzer made the acquaintance of attorneys William Patrick and Charles Phillip Johnson and surgeon Joseph Nash McDowell. Patrick and Johnson referred to Pulitzer as "Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

" because of his extraordinary profile. They helped him secure a job with the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad

The Atlantic and Pacific Railroad was a U.S. railroad that owned or operated two disjointed segments, one connecting St. Louis, Missouri with Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the other connecting Albuquerque, New Mexico with Needles in Southern Californi ...

. His work was to record the railroad land deeds in the twelve counties in southwest Missouri where the railroad planned to build a line. When he was done, the lawyers gave him desk space and allowed him to study law in their library to prepare for the bar.

Pulitzer displayed a flair for reporting. He would work 16 hours a dayfrom 10 am to 2 am. He was nicknamed "Joey the German" or "Joey the Jew". He joined the Philosophical Society and frequented a German bookstore where many intellectuals hung out. Among his new group of friends were Joseph Keppler

Joseph Ferdinand Keppler (February 1, 1838 – February 19, 1894) was an Austrian-born American cartoonist and caricaturist who greatly influenced the growth of satirical cartooning in the United States.

Early life

He was born in Vienna. His p ...

and Thomas Davidson.

Missouri State Representative

Pulitzer joined Schurz's Republican Party. On December 14, 1869, Pulitzer attended the Republican meeting at the St. Louis Turnhalle on Tenth Street, where party leaders needed a candidate to fill a vacancy in the state legislature. After their first choice refused, they settled on Pulitzer, nominating him unanimously, forgetting he was only 22, three years under the required age. However, his chief Democratic opponent was possibly ineligible because he had served in the Confederate army. Pulitzer had energy. He organized street meetings, called personally on the voters, and exhibited such sincerity along with his oddities that he had pumped a half-amused excitement into a campaign that was normally lethargic. He won 209–147. His age was not made an issue and he was seated as a state representative in Jefferson City at the session beginning January 5, 1870. During his time in Jefferson City, Pulitzer voted in favor of the adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment and led a crusade to reform the corrupt St. Louis County Court. His fight against the court angered Captain Edward Augustine, Superintendent of Registration for St. Louis County. Their rivalry became so heated that on the night of January 27, Augustine confronted Pulitzer at Schmidt's Hotel and called him a "damned liar." Pulitzer left the building, returned to his room, and retrieved a four-barreled pistol. He returned to the parlor and approached Augustine, renewing the argument. When Augustine advanced on Pulitzer, the young Representative aimed his pistol at the Captain's midriff. Augustine tackled Pulitzer, and the gun fired two shots, tearing through Augustine's knee and the hotel floor. Pulitzer suffered a head wound. Contemporary accounts conflict on whether Augustine was also armed. While in Jefferson City, Pulitzer also moved up one notch in the administration at the ''Westliche Post''. He eventually became its managing editor, and obtained a proprietary interest.Brian (2001)Break from the Republican Party and Schurz

On August 31, 1870, Schurz (now a U.S. Senator), Pulitzer, and other reformist anti-Grant Republicans bolted from the state convention at theCapitol

A capitol, named after the Capitoline Hill in Rome, is usually a legislative building where a legislature meets and makes laws for its respective political entity.

Specific capitols include:

* United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.

* Numerous ...

and nominated a competing Liberal Republican ticket for Missouri, led by the former Senator Benjamin Gratz Brown

Benjamin Gratz Brown (May 28, 1826December 13, 1885) was an American politician. He was a U.S. Senator, the 20th Governor of Missouri, and the Liberal Republican and Democratic Party vice presidential candidate in the presidential election of ...

. Brown was successful in the November election over the mainline Republican ticket, presenting a serious threat to President Grant's re-election chances. On January 19, 1872, Brown appointed Pulitzer to the St. Louis Board of Police Commissioners.

In May 1872, Pulitzer was a delegate to the Cincinnati convention of the Liberal Republican Party, which nominated ''New York Tribune'' editor Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressm ...

for the presidency with Gratz Brown as his running mate. Pulitzer and Schurz were expected to boost Governor Brown for the presidential nomination, but Schurz preferred the more idealistic Charles Francis Adams Sr.

Charles Francis Adams Sr. (August 18, 1807 – November 21, 1886) was an American historical editor, writer, politician, and diplomat. As United States Minister to the United Kingdom during the American Civil War, Adams was crucial to Union effort ...

A loyal Brown man alerted the Governor of this betrayal, and Governor Brown and his cousin Francis Preston Blair

Francis Preston Blair Sr. (April 12, 1791 – October 18, 1876) was an American journalist, newspaper editor, and influential figure in national politics advising several U.S. presidents across party lines.

Blair was an early member of the De ...

sped to Cincinnati to rally their supporters to Greeley.

While in Cincinnati, he met fellow reformist newspapermen Samuel Bowles, Murat Halstead

Murat Halstead (September 2, 1829 – July 2, 1908) was an American newspaper editor and magazine writer. He was a war correspondent during three wars.

Biography

Born in Paddy's Run (now Shandon), Ohio, in Butler County, Ohio, he was the son of G ...

, Horace White

Horace White (October 7, 1865 – November 27, 1943) was an American lawyer and politician from New York. He was the 37th Governor of New York from October 6, 1910 to December 31, 1910.

Life

He attended Syracuse Central High School, Cornell Un ...

, and Alexander McClure

Alexander Kelly McClure (January 9, 1828 – June 6, 1909) was an American politician, newspaper editor, and writer from Pennsylvania who served as a Republican member of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives from 1858 to 1859, the Pennsyl ...

. He also met Greeley's assistant and campaign manager Whitelaw Reid

Whitelaw Reid (October 27, 1837 – December 15, 1912) was an American politician and newspaper editor, as well as the author of ''Ohio in the War'', a popular work of history.

After assisting Horace Greeley as editor of the ''New-York Tribu ...

, who would become Pulitzer's journalistic adversary. However, Greeley's campaign was ultimately a disaster, and the new party collapsed, leaving Schurz and Pulitzer politically homeless.

In 1874, Pulitzer promoted a reform movement christened the People's Party, which united the Grange with dissident Republicans. However, Pulitzer was disappointed with the party's tepid stances on the issues and mediocre ticket, led by gentleman farmer William Gentry. He returned to St. Louis and endorsed the Democratic ticket. Pulitzer's own views were in line with Democratic orthodoxy on low tariffs, personal limited, and limited federal powers; his prior opposition to the Democrats was out of disgust for slavery and the Confederate rebellion. Pulitzer campaigned for the Democratic ticket throughout the state and published a damaging rumor (leaked by future Senator George Vest) that Gentry had sold a slave.

He also served as a delegate to the 1874 Missouri Constitutional Convention representing St. Louis, arguing successfully for true home rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

for the city.

In 1876, Pulitzer, by now completely disillusioned with the corruption of the Republicans and their nomination of Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

, gave nearly 70 speeches in favor of Democratic candidate Samuel J. Tilden throughout the country; Schurz, who saw Hayes as a reformer with integrity, returned to the Republican fold. In his speeches, Pulitzer denounced Schurz and urged reconciliation between North and South. While on his speaking tour, Pulitzer also wrote dispatches to the ''New York Sun

''The New York Sun'' is an American online newspaper published in Manhattan; from 2002 to 2008 it was a daily newspaper distributed in New York City. It debuted on April 16, 2002, adopting the name, motto, and masthead of the earlier New York ...

'' on behalf of the Tilden campaign. After Tilden's narrow defeat under dubious circumstances, Pulitzer became disillusioned with his candidate's indecision and timid response; he would oppose Tilden's 1880 run for the Democratic nomination. For now, he returned to St. Louis to practice law and search for future opportunities in news.

''St. Louis Post-Dispatch''

On his thirtieth birthday, Pulitzer's home at the Southern Hotel burned to the ground, likely destroying most of his personal belongings and papers. On December 9, 1878, Pulitzer bought the moribund ''St. Louis Dispatch'' and merged it with John Dillon's ''St. Louis Post'', forming the '' St. Louis Post and Dispatch'' (soon renamed the ''Post-Dispatch'') on December 12. With his own paper, Pulitzer developed his role as a champion of the common man, featuring exposés and a hard-hitting populist approach. The paper was considered a leader in the field of sensational journalism.Swanberg, ''Pulitzer'', p. 44 The circulation of the ''Post-Dispatch'' steadily rose during Pulitzer's early tenure (aided by the collapse of the city's other daily English-language paper, the ''Star''). At the time of merger, the Post and Dispatch had a combined circulation of under 4,000. By the end of 1879, circulation was up to 4,984 and Pulitzer doubled the size of the paper to eight pages. By the end of 1880, circulation was up to 8,740. Circulation rose dramatically to 12,000 by March 1881 and to 22,300 by September 1882. Pulitzer bought two new presses and increased staff pay to the highest in the city, though he also crushed an attempt to unionize.Political activism

Pulitzer's primary political rival at this time wasBourbon Democrat

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, especially those who su ...

William Hyde, publisher of the (misleadingly named) ''Missouri Republican''. Pulitzer's much smaller paper won a series of early political skirmishes over Hyde. First, George Vest was elected to the Senate in 1879 with Pulitzer's backing over Bourbon Samuel Glover. Next, Pulitzer secured election for an anti-Tilden delegation (including himself) to the 1880 Democratic National Convention

The 1880 Democratic National Convention was held June 22 to 24, 1880, at the Music Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio, and nominated Winfield S. Hancock of Pennsylvania for president and William H. English of Indiana for vice president in the United Stat ...

, over Hyde's objection. Though Pulitzer could not convince Horatio Seymour

Horatio Seymour (May 31, 1810February 12, 1886) was an American politician. He served as Governor of New York from 1853 to 1854 and from 1863 to 1864. He was the Democratic Party nominee for president in the 1868 United States presidential elec ...

, his preferred candidate, to run, the Democrats did not renominate Tilden. In March 1880, the two men even came to physical blows on Olive Street but were separated by a crowd before either was injured.

In 1880, Pulitzer made a second run for public office, this time for United States Representative from Missouri's second district. However, he was resoundingly defeated for the Democratic nomination (tantamount to victory in heavily Democratic St. Louis) by Bourbon Thomas Allen Thomas Allen may refer to:

Clergy

*Thomas Allen (nonconformist) (1608–1673), Anglican/nonconformist priest in England and New England

*Thomas Allen (dean of Chester) (died 1732)

*Thomas Allen (scholar) (1681–1755), Anglican priest in England

* ...

, 4,254 to 709.

Killing of Alonzo Slayback

When Thomas Allen died during his first term, Pulitzer's ''Post-Dispatch'' strongly opposed the ''Republican''James Broadhead

James Overton Broadhead (May 29, 1819 – August 7, 1898) was an American lawyer and political figure. He was a member of the House of Representatives and of the Missouri Senate, he was also the first president of the American Bar Association.Ro ...

, an attorney working for Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who is generally identified as one of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. His sharp and often unscrupulous business practices made him ...

. The election became heated, and ''Post-Dispatch'' managing editor John Cockerill called Broadhead's law partner Alonzo Slayback a "coward." Slayback entered the ''Post-Dispatch'' offices on October 13, armed with a gun, and threatened Cockerill; Cockerill shot him dead. The story became a national sensation and turned many conservative Democrats vehemently against Pulitzer and the ''Post-Dispatch''. After a grand jury inquest, Cockerill was never put on trial. Pulitzer replaced him with John Dillon, former owner of the ''Post'' and unlike Pulitzer and Cockerill, a well-respected, conservative native of the city. However, the incident permanently damaged Pulitzer's reputation in the city, and he began to seek opportunities elsewhere.

''New York World''

In April 1883, the Pulitzer family traveled to New York, ostensibly to launch a European vacation, but actually so that Joseph could make an offer to Jay Gould for ownership of the morning ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under publi ...

''. Gould had acquired the newspaper as a throw-in in one of his railroad deals, and it had been losing about $40,000 a year, possibly due to the stigma Gould's ownership brought. In return for the paper, Gould asked Pulitzer for a sum well over a half-million dollars, as well as the retention of the World's current staff and building. After some frustration at this request and disagreement with his brother Albert, Pulitzer was prepared to give up. At the urging of his wife Kate, however, he returned to negotiations with Gould. They agreed to a sale of $346,000 with Pulitzer retaining full freedom in the selection of staff.

The Pulitzers moved to New York full time, leasing a home in Gramercy Park. The World immediately gained 6,000 readers in its first two weeks under Pulitzer and had more than doubled its circulation to 39,000 within three months.

As he had in St. Louis, Pulitzer emphasized sensational stories: human-interest, crime, disasters, and scandal. Under Pulitzer's leadership, circulation grew from 15,000 to 600,000, making the ''World'' the largest newspaper in the country. Pulitzer emphasized broad appeal through short, provocative headlines and sentences; the World's self-described style was "brief, breezy and briggity." His ''World'' featured illustrations, advertising, and a culture of consumption for working men. Crusades for reform and entertainment news were two main staples for the ''World''.

In 1887, he recruited the famous investigative journalist

Investigative journalism is a form of journalism in which reporters deeply investigate a single topic of interest, such as serious crimes, political corruption, or corporate wrongdoing. An investigative journalist may spend months or years rese ...

Nellie Bly

Elizabeth Cochran Seaman (born Elizabeth Jane Cochran; May 5, 1864 – January 27, 1922), better known by her pen name Nellie Bly, was an American journalist, industrialist, inventor, and charity worker who was widely known for her record-breaki ...

.

Pulitzer was also involved with the construction of the New York World Building

The New York World Building (also the Pulitzer Building) was a building in the Civic Center of Manhattan in New York City, along Park Row between Frankfort Street and the Brooklyn Bridge. Part of the former " Newspaper Row", it was designed by ...

, designed by George B. Post and completed in 1890. Pulitzer dictated several aspects of the design, including the building's triple-height main entrance arch, dome, and rounded corner at Park Row and Frankfort Street.

In 1895, the ''World'' introduced the immensely popular ''The Yellow Kid

The Yellow Kid (Mickey Dugan) is an American comic strip character that appeared from 1895 to 1898 in Joseph Pulitzer's ''New York World'', and later William Randolph Hearst's ''New York Journal''. Created and drawn by Richard F. Outcault in t ...

'' comic by Richard F. Outcault

Richard Felton Outcault (; January 14, 1863 – September 25, 1928) was an American cartoonist. He was the creator of the series ''The Yellow Kid'' and ''Buster Brown'' and is considered a key pioneer of the modern comic strip.

Life and career

...

, one of the first strips to be featured in the newly launched Sunday color supplement shortly after.

After the ''World'' exposed an illegal payment of $40,000,000 by the United States to the French Panama Canal Company

The Panama Canal Zone ( es, Zona del Canal de Panamá), also simply known as the Canal Zone, was an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the Isthmus of Panama, that existed from 1903 to 1979. It was located within the terr ...

in 1909, Pulitzer was indicted for libeling Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

and J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age. As the head of the banking firm that ultimately became known ...

. The courts dismissed the indictments.

Newspaper writer and editor of ''The San Francisco Call, '' John McNaught went to New York to work under Pulitzer as his personal secretary from 1907 to 1912. When McNaught left ''The Evening World,'' he became editor of the ''New York World,'' through 1915.

Early political activism

When Pulitzer purchased the ''World'', New York City, though overwhelmingly Democratic, did not have a major Democratic newspaper. The ''Tribune'' (under Whitelaw Reid) and ''Times'' were ardently Republican and the ''Sun'' (under Charles Dana) and ''Herald'' were independent In the first issue under his ownership, Pulitzer announced the paper would be "dedicated to the cause of the people rather than that of purse-potentates." In 1884, he joined the Manhattan Club, a group of wealthy Democrats including Tilden,Abram Hewitt

Abram Stevens Hewitt (July 31, 1822January 18, 1903) was an American politician, educator, ironmaking industrialist, and lawyer who was mayor of New York City for two years from 1887–1888. He also twice served as a U.S. Congressman from an ...

, and William C. Whitney. Through the ''World'', he supported the campaign of New York Governor Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

for president. Pulitzer's campaign for Cleveland and against Republican James G. Blaine may have been pivotal in securing the presidency for Cleveland, who won New York's decisive votes by just 0.1%. The campaign also boosted the ''World''Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

as a "reform fraud," beginning a long and heated rivalry with the future President.

United States House of Representatives

In 1884, Pulitzer was elected to theU.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

from New York's ninth district as a Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

and entered office on March 4, 1885.

Though inundated with office-seekers hoping for appointment by President-elect Cleveland, Pulitzer recommended only the appointments of Charles Gibson for Minister to Berlin and Pallen as consul general in London. But Pulitzer did not secure a meeting with the President-elect, and neither man was appointed.

During his term in office, Pulitzer led a crusade to place the newly gifted Statue of Liberty

The Statue of Liberty (''Liberty Enlightening the World''; French: ''La Liberté éclairant le monde'') is a List of colossal sculpture in situ, colossal neoclassical sculpture on Liberty Island in New York Harbor in New York City, in the U ...

in New York City. He was a member of the Committee on Commerce

The United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation is a standing committee of the United States Senate. Besides having broad jurisdiction over all matters concerning interstate commerce, science and technology policy, a ...

.

During his time in Washington, Pulitzer lived at the luxurious hostel run by John Chamberlin at the corner of 15th and I Streets. However, Pulitzer soon determined that his position at the ''World'' was both more powerful and more enjoyable than Congress. He began to spend less and less time in Washington, and ultimately resigned on April 10, 1886, after little over a year in office.

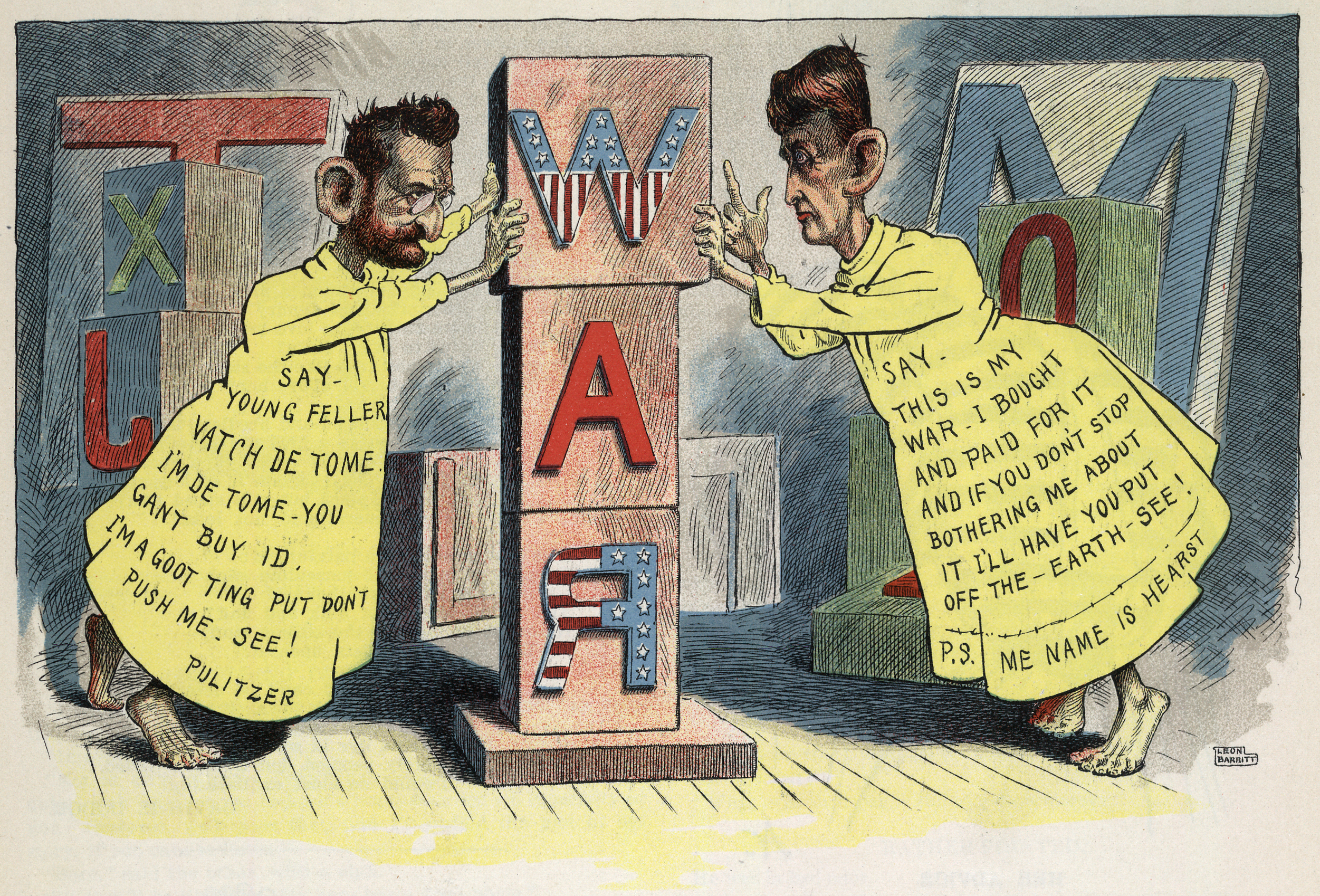

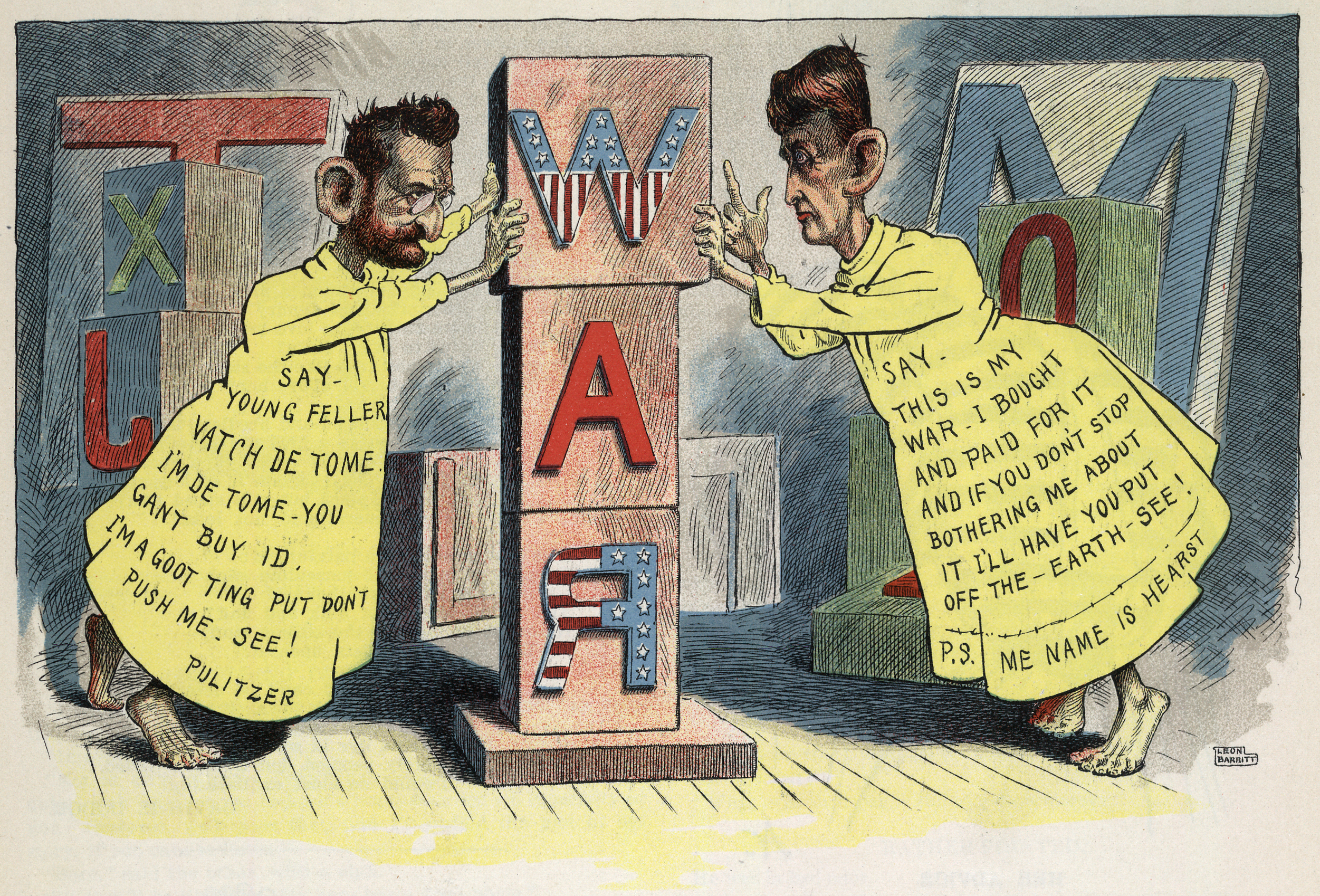

Rivalry with William Randolph Hearst

In 1895,

In 1895, William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

purchased the rival ''New York Journal

:''Includes coverage of New York Journal-American and its predecessors New York Journal, The Journal, New York American and New York Evening Journal''

The ''New York Journal-American'' was a daily newspaper published in New York City from 1937 t ...

'', which at one time had been owned by Pulitzer's brother, Albert

Albert may refer to:

Companies

* Albert (supermarket), a supermarket chain in the Czech Republic

* Albert Heijn, a supermarket chain in the Netherlands

* Albert Market, a street market in The Gambia

* Albert Productions, a record label

* Alber ...

. Hearst had once been a great admirer of Pulitzer's ''World''. The two embarked on a circulation war. This competition with Hearst, particularly the coverage before and during the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

, linked Pulitzer's name with yellow journalism

Yellow journalism and yellow press are American terms for journalism and associated newspapers that present little or no legitimate, well-researched news while instead using eye-catching headlines for increased sales. Techniques may include e ...

.

Pulitzer and Hearst were also the cause of the newsboys' strike of 1899

The newsboys' strike of 1899 was a U.S. youth-led campaign to facilitate change in the way that Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst's newspapers compensated their force of newsboys or newspaper hawkers. The strikers demonstrated across N ...

, a youth-led campaign to force change in the way that Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst's newspapers compensated their child newspaper hawkers.

Other rivals

Charles A. Dana, the editor of the rival ''New York Sun

''The New York Sun'' is an American online newspaper published in Manhattan; from 2002 to 2008 it was a daily newspaper distributed in New York City. It debuted on April 16, 2002, adopting the name, motto, and masthead of the earlier New York ...

'' and personal enemy of Grover Cleveland, became estranged from Pulitzer during the 1884 campaign. Dana's ''Sun'' endorsed Greenback nominee Benjamin Butler

Benjamin Franklin Butler (November 5, 1818 – January 11, 1893) was an American major general of the Union Army, politician, lawyer, and businessman from Massachusetts. Born in New Hampshire and raised in Lowell, Massachusetts, Butler is best ...

, a major blow in swing state New York. He attacked Pulitzer in print, often calling him "Judas Pulitzer." After Cleveland's victory, the Sun's circulation had been halved and the ''World'' replaced it as the largest Democratic paper in the country.

Leander Richardson

Leander Pease Richardson (February 28, 1856 – February 2, 1918) was an American journalist, playwright, theatrical writer and author.The Journalist,'' was even more directly antisemitic, referring to his former boss only as "Jewseph Pulitzer."

Whitelaw Reid frequently sparred with Pulitzer, both in person and in their respective papers.

Don Carlos Seitz Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott Company 1916. p. 66

online edition

* Ireland, Alleyne

''Joseph Pulitzer: Reminiscences of a Secretary''

(1914) * Morris, James McGrath. ''Pulitzer: A Life in Politics, Print and Power'' (2010), a scholarly biography. * Morris, James McGrath. "The Political Education of Joseph Pulitzer," ''Missouri Historical Review'', Jan 2010, Vol. 104 Issue 2, pp. 78–94 * Retrieved on 2008-11-06 * * Rammelkamp, Julian S. '' Pulitzer's Post-Dispatch 1878–1883'' (1967) *

Nellie Bly Online

* ttps://www.lambiek.net/artists/p/pulitzer_joseph.htm Lambiek Comiclopedia article.* {{DEFAULTSORT:Pulitzer, Joseph 1847 births 1911 deaths People from Makó Hungarian Jews American people of Hungarian-Jewish descent New York (state) Republicans New York (state) Liberal Republicans Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state) Jewish members of the United States House of Representatives Columbia University people 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people) 19th-century Hungarian people Jewish American military personnel American newspaper chain founders American male journalists Naturalized citizens of the United States Blind people from the United States Hungarian journalists Members of the Missouri House of Representatives Politicians from St. Louis People of New York (state) in the American Civil War People of the Spanish–American War

Declining health and resignation

Pulitzer's health problems (blindness, depression, and acute noise sensitivity) caused a rapid deterioration, and he had to withdraw from the daily management of the newspaper. He continued to manage the paper from his New York mansion, his winter retreat at theJekyll Island Club

The Jekyll Island Club was a private club on Jekyll Island, on Georgia's Atlantic coast. It was founded in 1886 when members of an incorporated hunting and recreational club purchased the island for $125,000 (about $3.1 million in 2017) from John ...

on Jekyll Island, Georgia

Jekyll Island is located off the coast of the U.S. state of Georgia, in Glynn County. It is one of the Sea Islands and one of the Golden Isles of Georgia barrier islands. The island is owned by the State of Georgia and run by a self-sustaining, ...

, and his summer vacation retreat in Bar Harbor, Maine.

After he hired Frank I. Cobb (1869–1923) in 1904 as the editor of the New York ''World'', the younger man resisted Pulitzer's attempts to "run the office" from his home. Time after time, they battled each other, often with heated language.

When Pulitzer's son took over administrative responsibility in 1907, Pulitzer wrote a carefully worded resignation. It was printed in every New York paper except the ''World''. Pulitzer was insulted but slowly began to respect Cobb's editorials and independent spirit. Their exchanges, commentaries, and messages increased. The good rapport between the two was based largely on Cobb's flexibility. In May 1908, Cobb and Pulitzer met to outline plans for a consistent editorial policy but it wavered on occasion.

Pulitzer's demands for editorials on contemporary breaking news led to overwork by Cobb. Pulitzer sent him on a six-week tour of Europe to restore his spirit. Cobb continued the editorial policies he had shared with Pulitzer until Cobb died of cancer in 1923.

In a company meeting, Professor Thomas Davidson said, "I cannot understand why it is, Mr. Pulitzer, that you always speak so kindly of reporters and so severely of all editors." "Well", Pulitzer replied, "I suppose it is because every reporter is a hope, and every editor is a disappointment."

This phrase became an epigram

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, and sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word is derived from the Greek "inscription" from "to write on, to inscribe", and the literary device has been employed for over two mille ...

of journalism."Training for the Newspaper Trade"Don Carlos Seitz Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott Company 1916. p. 66

Marriage and family

In 1878 at the age of 31, Pulitzer married Katherine "Kate" Davis (1853–1927), a woman of high social standing from Georgetown, District of Columbia. She was five years younger than Pulitzer, from an Episcopalian family, and rumored to be a distant relative ofJefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a ...

. They married in an Episcopal ceremony at the Church of the Epiphany in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

He did not reveal his Jewish heritage to Katherine or her family until after their marriage, to her shock.

Of seven children, five lived to adulthood: Ralph

Ralph (pronounced ; or ,) is a male given name of English, Scottish and Irish origin, derived from the Old English ''Rædwulf'' and Radulf, cognate with the Old Norse ''Raðulfr'' (''rað'' "counsel" and ''ulfr'' "wolf").

The most common forms ...

, Joseph Jr. (father of Joseph Pulitzer III), Constance Helen (1888–1938), who married William Gray Elmslie, D.D. Edith (1886–1975), who married William Scoville Moore, and Herbert, eventually his brother Ralph's partner at the ''Post''. Their daughter, Katherine Ethel Pulitzer, died of pneumonia in May 1884 at age 2. On December 31, 1897, their older daughter, Lucille Irma Pulitzer, died at the age of 17 from typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

. An Irish immigrant named Mary Boyle largely raised the children while their parents were busy.

Pulitzer's grandson, Herbert Pulitzer, Jr. was married to the American fashion designer and socialite Lilly Pulitzer

Lillian Pulitzer Rousseau (November 10, 1931 – April 7, 2013) was an American entrepreneur, fashion designer, and socialite. She founded Lilly Pulitzer, Inc., which produces floral print clothing and other wares.

Career

Lilly and husband H ...

.

Following a fire at his former residence, Pulitzer commissioned Stanford White

Stanford White (November 9, 1853 – June 25, 1906) was an American architect. He was also a partner in the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, one of the most significant Beaux-Arts firms. He designed many houses for the rich, in additio ...

to design a limestone-clad Venetian palazzo at 11 East 73rd Street on the Upper East Side

The Upper East Side, sometimes abbreviated UES, is a neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 96th Street to the north, the East River to the east, 59th Street to the south, and Central Park/Fifth Avenue to the wes ...

; it was completed in 1903. Pulitzer's thoughtful seated portrait by John Singer Sargent

John Singer Sargent (; January 12, 1856 – April 14, 1925) was an American expatriate artist, considered the "leading portrait painter of his generation" for his evocations of Edwardian-era luxury. He created roughly 900 oil paintings and more ...

is at the Columbia School of Journalism that he founded.

The family continued to be involved in the operation of the St. Louis paper for several generations until April 1995, when Joseph Pulitzer IV resigned from the paper in a management dispute. His daughter (Joseph J. Pulitzer's great-great-granddaughter) Elkhanah Pulitzer is an opera director.

Death

For six months during 1908, Pulitzer was attended to by his personal physicianC. Louis Leipoldt

Christian Frederik Louis Leipoldt ( ; 28 December 1880 – 12 April 1947), usually referred to as C. Louis Leipoldt, was a South African poet, dramatist, medical doctor, reporter and food expert. Together with Jan F. E. Celliers and Totius (poe ...

aboard his yacht ''Liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

''. While traveling to his winter home at the Jekyll Island Club

The Jekyll Island Club was a private club on Jekyll Island, on Georgia's Atlantic coast. It was founded in 1886 when members of an incorporated hunting and recreational club purchased the island for $125,000 (about $3.1 million in 2017) from John ...

on Jekyll Island, Georgia

Jekyll Island is located off the coast of the U.S. state of Georgia, in Glynn County. It is one of the Sea Islands and one of the Golden Isles of Georgia barrier islands. The island is owned by the State of Georgia and run by a self-sustaining, ...

, in 1911, Pulitzer had his yacht stop in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

. On October 29, 1911, Pulitzer listened to his German secretary read aloud about King Louis XI

Louis XI (3 July 1423 – 30 August 1483), called "Louis the Prudent" (french: le Prudent), was King of France from 1461 to 1483. He succeeded his father, Charles VII.

Louis entered into open rebellion against his father in a short-lived revol ...

of France. As the secretary neared the end, Pulitzer said in German: ''"Leise, ganz leise"'' (English: "Softly, quite softly"), and died. His body was returned to New York for services and interred in the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx

The Bronx () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the state of New York. It is south of Westchester County; north and east of the New York City borough of Manhattan, across the Harlem River; and north of the New Y ...

.

Legacy

Journalism schools

In 1892, Pulitzer offeredColumbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

's president, Seth Low

Seth Low (January 18, 1850 – September 17, 1916) was an American educator and political figure who served as the mayor of Brooklyn from 1881 to 1885, the president of Columbia University from 1890 to 1901, a diplomatic representative of t ...

, money to set up the world's first school of journalism. The university initially turned down the money. In 1902, Columbia's new president Nicholas Murray Butler

Nicholas Murray Butler () was an American philosopher, diplomat, and educator. Butler was president of Columbia University, president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, and the deceased Ja ...

was more receptive to the plan for a school and journalism prizes, but it would not be until after Pulitzer's death that this dream would be fulfilled.

Pulitzer left the university $2,000,000 in his will. In 1912, the school founded the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism

The Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism is located in Pulitzer Hall on the university's Morningside Heights campus in New York City.

Founded in 1912 by Joseph Pulitzer, Columbia Journalism School is one of the oldest journalism s ...

. This followed the Missouri School of Journalism

The Missouri School of Journalism at the University of Missouri in Columbia is one of the oldest formal journalism schools in the world. The school provides academic education and practical training in all areas of journalism and strategic comm ...

, founded at the University of Missouri

The University of Missouri (Mizzou, MU, or Missouri) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Columbia, Missouri. It is Missouri's largest university and the flagship of the four-campus Universit ...

with Pulitzer's urging. Both schools remain among the most prestigious in the world.

Pulitzer Prize

In 1917, Columbia organized the awards of the firstPulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

s in journalism. The awards have been expanded to recognize achievements in literature, poetry, history, music, and drama.

Legacy and honors

* TheU.S. Post Office

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or Postal Service, is an Independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the executive branch of the Federal government of the Uni ...

issued a 3-cent stamp commemorating Joseph Pulitzer in 1947, the 100th anniversary of his birth.

* The Pulitzer Arts Foundation

Pulitzer Arts Foundation is an art museum in St. Louis, Missouri, that presents special exhibitions and public programs. Known informally as the Pulitzer, the museum is located at 3716 Washington Boulevard in the Grand Center Arts District. The ...

in Saint Louis was founded by his family's philanthropy and is named in their honor.

* In 1989 Joseph Pulitzer was inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame

The St. Louis Walk of Fame honors notable people from St. Louis, Missouri, who made contributions to the culture of the United States. All inductees were either born in the Greater St. Louis area or spent their formative or creative years ther ...

.

* He is featured as a character in the Disney film '' Newsies'' (1992), in which he was played by Robert Duvall

Robert Selden Duvall (; born January 5, 1931) is an American actor and filmmaker. His career spans more than seven decades and he is considered one of the greatest American actors of all time. He is the recipient of an Academy Award, four Gold ...

, and the Broadway stage production ('' Newsies'') adapted from it which was produced in 2011.

* In the 2014 historical novel, ''The New Colossus,'' by Marshall Goldberg, published by Diversion Books, Joseph Pulitzer gives reporter Nellie Bly

Elizabeth Cochran Seaman (born Elizabeth Jane Cochran; May 5, 1864 – January 27, 1922), better known by her pen name Nellie Bly, was an American journalist, industrialist, inventor, and charity worker who was widely known for her record-breaki ...

the assignment of investigating the death of poet Emma Lazarus

Emma Lazarus (July 22, 1849 – November 19, 1887) was an American author of poetry, prose, and translations, as well as an activist for Jewish and Georgist causes. She is remembered for writing the sonnet "The New Colossus", which was inspired ...

.

* The Hotel Pulitzer in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

was named after his grandson Herbert Pulitzer.

* Mount Pulitzer in Washington state is named for him.

See also

* Joseph Pulitzer House *Place des États-Unis

The Place des États-Unis (; "United States Square") is a public space in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, France, about 500 m south of the Place de l'Étoile and the Arc de Triomphe.

It consists of a plaza, approximately long and wide, tre ...

* Pulitzer Arts Foundation

Pulitzer Arts Foundation is an art museum in St. Louis, Missouri, that presents special exhibitions and public programs. Known informally as the Pulitzer, the museum is located at 3716 Washington Boulevard in the Grand Center Arts District. The ...

* List of Jewish members of the United States Congress

Notes

References

; Sources * Brian, Denis. ''Pulitzer: A Life'' (2001online edition

* Ireland, Alleyne

''Joseph Pulitzer: Reminiscences of a Secretary''

(1914) * Morris, James McGrath. ''Pulitzer: A Life in Politics, Print and Power'' (2010), a scholarly biography. * Morris, James McGrath. "The Political Education of Joseph Pulitzer," ''Missouri Historical Review'', Jan 2010, Vol. 104 Issue 2, pp. 78–94 * Retrieved on 2008-11-06 * * Rammelkamp, Julian S. '' Pulitzer's Post-Dispatch 1878–1883'' (1967) *

External links

* Original New York World articles aNellie Bly Online

* ttps://www.lambiek.net/artists/p/pulitzer_joseph.htm Lambiek Comiclopedia article.* {{DEFAULTSORT:Pulitzer, Joseph 1847 births 1911 deaths People from Makó Hungarian Jews American people of Hungarian-Jewish descent New York (state) Republicans New York (state) Liberal Republicans Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state) Jewish members of the United States House of Representatives Columbia University people 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people) 19th-century Hungarian people Jewish American military personnel American newspaper chain founders American male journalists Naturalized citizens of the United States Blind people from the United States Hungarian journalists Members of the Missouri House of Representatives Politicians from St. Louis People of New York (state) in the American Civil War People of the Spanish–American War

Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

St. Louis Post-Dispatch people

Union Army soldiers

Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York)

Statue of Liberty

19th-century American politicians

Hungarian emigrants to the United States

Former yacht owners of New York City

Members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state)